Casualties in Perspective

The sacrifices of the people of Brantford, Brant County and Six Nations are epitomized by the following stories.

The First Casualty

On October 1st, 1914, Pte. Arthur Barnes became the first local casualty in the Great War. He was hit by a shell and was so severely wounded and in so much pain he pleaded for his death to his friend. “For God's sake, shoot me Jack. I can't stand the pain,” he begged of John Cobden.

A reservist with the Coldstream Guards, Barnes was a Brantford resident who had returned to the Old Country to fight for King and Country in the First World War. After a couple of days in hospital, Barnes succumbed to his injuries. He became the first Brantford-Brant County resident to die in the Great War.[1]

Very few people remember Arthur Barnes today. The name Cameron Brant, however, is instantly recognized, even to this day.

An Iconic Casualty

“We in common with the rest of our province have been deeply touched by the falling in battle of Lieut. Cameron D. Brant, the direct lineal descendant of your illustrious chief, whose name is so highly esteemed and honored throughout our country.”

A splendid officer, full of energy and resourcefulness, Lieutenant Cameron D. Brant, was among the first Six Nations/New Credit men to enlist for service overseas following the outbreak of war. He was also the first to die.

Brant was killed on the night of the 24th of April 1915 at the First Battle of Ypres. He was also the first non-British reservist casualty of the war from Brant County.[2] This loss further united the respective war efforts of Six Nations/New Credit and Brantford/Brant County.

Cameron Brant was born at New Credit August 12, 1887. He was a direct descendent of Joseph Brant (great-great-grandson), and was educated at the New Credit and Hagersville high schools. Upon graduation, Brant pursued military training at Wolseley Barracks in London, Ontario. After his return to New Credit, he enlisted with 37th Haldimand Rifles in 1906, but resigned in 1912 to pursue employment in Hamilton, while settling on a farm in Hagersville with his wife, Florence (Flossie).

Three days after the declaration of war Brant re-enlisted along with his cousins Frank Montour and Elgin Brant.[3] Cameron was promoted to Lieutenant while training with the 4th Battalion at Valcartier, and he was sent overseas in February 1915. At the age of 28, Cameron Brant was killed in action, leaving his wife, parents, and nine siblings to mourn his loss.

The news travelled relatively quickly for that era. On April 26, 1915, within two days of his death, Florence was informed of her husband’s fate. While still reeling from the news, she received letters he had written previously. The detailed account of how Florence discovered her husband had been killed is in The Brantford Expositor.[4]

The death of Cameron Brant sent shockwaves through the Brantford, Brant County, and Six Nations communities. The Brantford Expositor printed seven articles dedicated to Brant immediately after his death. Many of these emphasized his family connection to Joseph Brant and Six Nations’ historic military service to the British Crown.[5]

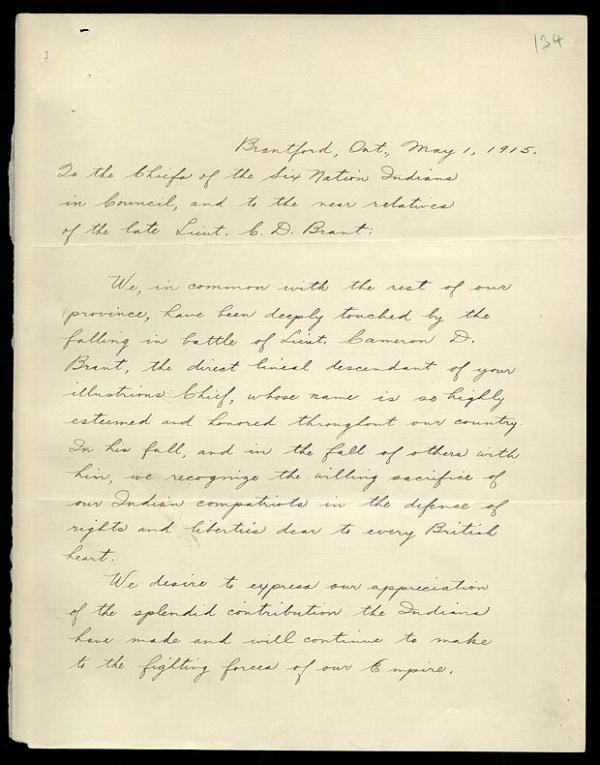

On May 4, 1915, after the passing of a resolution by the Six Nations Confederacy Council, Chief A.G. Smith performed a traditional condolence ceremony for Brant and his family, emphasizing Brant’s sacrifice and the alliance between the Six Nations and the British Crown.[6] On May 1, 1915, the City of Brantford and Brant County sent the Chiefs of Six Nations and Brant’s family a letter of condolence, which was also printed in The Expositor.

This letter began:

To the Chiefs of the Six Nations Indians in Council, and the near relatives of the late Lieut. C.D. Brant:

We in common with the rest of our province have been deeply touched by the falling in battle of Lieut. Cameron D. Brant, the direct lineal descendant of your illustrious chief, whose name is so highly esteemed and honored throughout our country. In his fall, and in the fall of others with him, we recognize the willing sacrifice of our Indian compatriots in the defense of rights and liberties dear to every British

We desire to express our appreciation of the splendid contribution the Indians have made and will continue to make to the fighting forces of our Empire.

Finally, in August 1915, a letter was sent to Rev. G.A. Woodside from Rev. Wm. Beattie, the Chaplain of 1st Brigade C.E.F., which stated that Brant “was a splendid officer and so full of energy and resourcefulness. He was beloved by all. His death, coming at the time it did, robbed the battalion of an officer we could very ill spare. I would like if you would make known to his relatives the very high regard we all held him and our proud admiration of his fearless conduct on that and all other occasions.”[7]

Brant would later be memorialized on the Meinn Gate in Ypres, the Six Nations Honour Roll, the Brant County Cenotaph, on a memorial at the New Credit Methodist Church, and with the “Mad Fourth” Honour Shield, commemorating the memory of Brant and all the early Six Nations enlistees, many of who enlisted with the 4th battalion.[8]

The Youngest Casualty

Private Sam Chickegian was among the youngest Brantford residents to die fighting for Canada in the First World War. He was the 15-year-old son of Mr. and Mrs. John Chickegian, an Armenian couple who had come to Canada in 1907. They moved to Alfred Street, Brantford from St. Catharines.

When the First World War broke out, Sam lied about his age and ran away from home to enlist with the Canadian Expeditionary Force overseas. He was in France when his commanding officer received a letter from Sam's mother and learned that he was just 15. Sam was given an opportunity to return home but he declined.

"The officer called me up and asked me about the letter you wrote him. He asked me if I wanted to go back, but I said 'No.' I know you must be worried mother, but there is no use trying to get me to quit when I've come so far. I am going to do my share."

On September 2, 1918, Chickegian was killed in action south west of Buissy while advancing with his battalion.

The Last Casualty

An American by birth, Private Kenneth Lawrence was living at 71 Gilkison St. Brantford, when the First World War broke out. He joined the Canadian Expeditionary Force overseas and was fighting in France on Nov. 11, 1918. The Armistice had been signed at 5 a.m. that day and came into effect at 11 a.m. Lawrence was wounded at about 10:45 a.m. - 15 minutes before the Armistice came into effect.

An American by birth, Private Kenneth Lawrence was living at 71 Gilkison St. Brantford, when the First World War broke out. He joined the Canadian Expeditionary Force overseas and was fighting in France on Nov. 11, 1918. The Armistice had been signed at 5 a.m. that day and came into effect at 11 a.m. Lawrence was wounded at about 10:45 a.m. - 15 minutes before the Armistice came into effect.

Lawrence recovered from his wounds and he returned to Brantford. He married Eva Frey in the fall of 1921. A watchmaker, Lawrence and his wife moved to Buffalo, New York in 1924. At that time, they had a son named Earnest.

Figures compiled by Statistics Canada state that 34,496 Canadians were killed in action from 1914 to 1918 and during that time period another 17,182 died as a result of wounds. An additional 4,960 Canadians were presumed dead. There were also 132,550 Canadians wounded in the First World War.[9]

[1] Vincent Ball (research by Geoffrey Moyer) “Lest We Forget” The Brantford Expositor, Nov. 11, 2011.

[2] The Brantford Expositor, May 7, 1915.

[3] Donald B. Smith, "Brant, Cameron Dee" Canadian Dictionary of Biography (Toronto and Quebec City: University of Toronto and Laval University, 1998) and Draft Copy of the Warriors Exhibit Resource Guide, Woodland Cultural Centre, Warrior Files.

[4] The Brantford Expositor, April 30, 1915.

[5] The Brantford Expositor, April 26, 1915, April 27, 1915, April 30, 1915, May 1, 1915, May 6, 1915, May 7, 1915, and August 16, 1915.

[6] Six Nations Council Minutes from May 4, 1915 (RG 10, Vol. 1739, File 63-32 Part 4, Reel C-15023 Minutes of Six Nations Council – Six Nations 1894-1915).

[7] The Brantford Expositor, August 16, 1917.

[8] Smith and The Brantford Expositor June 18, 1919.