Great War Monuments - Brantford

An unprecedented conflict like the Great War was bound to inspire a determination to solemnly remember all those who had perished. The same pride and loyalty that motivated enlistment also fuelled the desire to commemorate. There might be debates about the type of monument that was most suitable, but few disagreed that some recognition was essential.

The scale of the suffering and sacrifice was so large, the selflessness with which average men and women responded to the call was so inspiring, that people made a conscious decision early in the War that those who served must be remembered.

The first commemoration on a grand scale was proposed in November 1917. The Brantford Expositor announced that “The contract has been let for the handsome new monument to be erected in the Odd Fellows’ Plot at Mt. Hope Cemetery….The new stone, which will be 14 feet in height and six feet wide at the base, will be one of the most pretentious in the city…”[1] The newspaper gave extensive coverage to the unveiling ceremony the following year. On September 9 The Expositor reported:

In solemn dedication, which carried a stirring inspiration to thousands gathered together for the ceremony, Reverend Walter Cox, Grand Master of the Odd Fellows of Ontario on Sunday afternoon unveiled the memorial to the memory of the Odd Fellows of Brantford who have made the extreme sacrifice in the Great War. As the Union Jack which enfolded the majestic appearing monument was impressively lifted and flung to the breeze, thousands who crowded into Mt. Hope Cemetery felt a thrill of pride and of patriotism. The memorial in its solidity, splendor and quiet beauty typified to all the story of the sacrifice for which it was raised….It was the first war memorial to be raised in Brantford, and as such will always hold a distinct place in the thoughts and activities of Odd Fellowship, the strength of which was never more impressively shown that in the great procession of members on Sunday…[2]

In his oration, Grand Master Reverend Walter Cox of Gananoque addressed the approximately 700 participants gathered for the event. Cox stated that:

…the hearts of everyone went out to those who had lost dear ones in the Great War, but they could be envied for the name which they had left. Our men, who had gone to fight, did not go to win territory, to kill Germans or to destroy generally, but [that] we who were left might live in peace and go about our business with good will to all. Behind him stood the memento, imperishable and ineffaceable, to those who lay in Flanders fields. They had laid down their lives, but they should be among the first whom we would rejoin on the great Resurrection Day. Then followed the unveiling, after which four little girls fastened a huge floral wreath to a royal purple ribbon surrounding the monument, while the speaker paused amid a reverent silence.[3]

A couple of elements are worth noting here. One is what the writer, Paul Fussell, has called “high diction”.[4] In words like “imperishable” and “ineffaceable”, and phrases such as “laid down their lives”, the speaker is referring to the suffering of war in elevated language that was not going to offend his audience. There would be no talk of scattered limbs, huge rats or men crying out in No Man’s Land in these ceremonies.

Another noteworthy element is the allusion to Christianity. The sacrifices of the soldiers are identified with the sacrifices of Jesus Christ in order to underline their higher purpose. Finally, the involvement of children in the unveiling ceremony is typical. The young were there to symbolize innocence and purity and point to the continuity between the values and aspirations of the men who served and future generations of Canadians.

The Odd Fellows’ effort to reflect and remember echoed elsewhere in town. It was at about this time that first mention was made of a general plan to commemorate soldiers in a special section of Mount Hope. On November 1, 1918 The Expositor reported:

Mr. John H. Spence, chairman of the Patriotic Association, announced today that the association proposed to act jointly with the G.W.V.A. in having interment of the bodies of all soldiers who had passed away recently and who were now in individual plots in Mt. Hope Cemetery, made in one plot, and when the war was over and circumstances were auspicious, to have a shaft erected over these graves with the names of all the deceased inscribed.[5]

It was a decade before these plans came to fruition. All sorts of ingenuity in the raising of funds was required and those behind the project proved themselves up to the task, even resorting to card parties in order to raise money.

On Sept. 23, 1928 the soldiers’ plot was finally ready. The Expositor described the inauguration, noting:

The unveiling on Sunday of a suitable memorial in Mount Hope Cemetery, to make the last resting places of returned soldiers, was very properly attended by thousands of citizens. There never can be enough adequate recognition of the valor of the men who helped to hold high the torch of liberty during a time of great world crisis. In addition to those who died so valiantly upon the field of struggle, the levy has been constant upon those returning to civil life by reason of wounds and hardships they encountered as many mounds so eloquently tell. It is at this time well worth recalling that from this community of Brantford and Brant County 5,571 – including 37 nurses – donned the uniform, and that of these 608 officers and men gave their lives for the cause; 58 were reported missing, hundreds were wounded and 143 won decorations or were mentioned in dispatches. Our number was the largest per capita of any section in Canada, and the living should never forget the wonderful record of courage and self-sacrifice on behalf of the Empire. Members of the Eagle Place Kith and Kin, to whose initiative the memorial is due, will be the recipients of much felicitation upon their completion of a most worthy enterprise.[6]

The speaker went on to point out the significance of the construction and design of the monument, the lasting combination of the materials of which it was made, Scottish and Canadian granite, being symbolic of Empire unity. The sheathed sword on each of the four sides of the shaft was the emblem of everlasting peace for those whose resting place it marked. The sides were identical, facing the four corners of the earth, each side bearing the inscriptions: “Their Name Liveth Forevermore,” and the motto of the Kith and Kin “Lest We Forget.” No names were engraved upon the stone, significant that those for whom it was erected went not to war to make great names for themselves, but with the spirit of service and sacrifice. Inscribed elsewhere, in the Great Book of Days, “Their Name Liveth Forevermore.”[7]

The speaker went on to point out the significance of the construction and design of the monument, the lasting combination of the materials of which it was made, Scottish and Canadian granite, being symbolic of Empire unity. The sheathed sword on each of the four sides of the shaft was the emblem of everlasting peace for those whose resting place it marked. The sides were identical, facing the four corners of the earth, each side bearing the inscriptions: “Their Name Liveth Forevermore,” and the motto of the Kith and Kin “Lest We Forget.” No names were engraved upon the stone, significant that those for whom it was erected went not to war to make great names for themselves, but with the spirit of service and sacrifice. Inscribed elsewhere, in the Great Book of Days, “Their Name Liveth Forevermore.”[7]

The Soldiers’ Plot became a beloved feature of the cemetery and was expanded on more than one occasion. In 1928 The Expositor explained that it had “…been added to by two or three successive grants until now it has space for more than 450.” The plot included some 46 veterans of “…campaigns from Egypt, India, Sudan, South Africa, and various theatres of hostilities in the last war. There are also about six women and children who died of influenza during the epidemic of 1917-1918, while their husbands and fathers were overseas.”[8]

Commemoration of the glorious dead could take many forms. Indeed, around the Empire, there were debates about the relative merits of practical vs. purely ornamental monuments. Swimming pools, libraries, community halls and other amenities were often championed by those who thought that the sacrifices of common men and women should be recognized by making the lives of their comrades who survived easier and more pleasant.

Brantford was no stranger to these discussions. And one of the lasting monuments to the Great War was utilitarian[9] in nature: Major Ballachey School. In 1919 the Board of Education decided to name its new facility in the East Ward after this slain veteran. As The Expositor reported the Chairman outlined a number of reasons for this decision:

This is the first school in Brantford to be built since the signing of the armistice. It will be opened in what will be known as ‘Peace Year.’ Can anything be more fitting than that the name of this school should be most closely connected with those men from our city who made this peace year possible. To do so will be public recognition of the great debt this community owes to its fighting men as well as recognition of those who will not return, thereby providing a lasting, living and just memorial to all of Brantford’s noble heroes. This being granted, who of all the men should give his name to this school? All are worthy without exception, yet one only can be chosen as representing all the others. By a process of just elimination we come to the name of one who was for many years a member of this board and, who was always deeply interested in educational matters in this city – P.P. Ballachey. So far as we can gather Major Ballachey was the only one of all the members of the Board of Education of this city who paid the supreme sacrifice.[10]

Despite the victory of the utilitarians in this instance, The Expositor remained unconvinced, arguing that it was:

…beyond the scope of true sentiment and duty to associate the suggestions of a municipal building, convention hall, court house, sanatorium, bridge, and numerous similar public utility prospects, with the true ideals of memorials. Such memorials as these are public utilities distinct from other consideration.

If true appreciation is to be expressed, utilitarian purposes must be entirely excluded. The true message cannot be carried by things adopted for public use. If their first identity is almost wholly public use it follows that any semblance of identity as is a memorial becomes almost immediately lost in the elemental mass of human pursuits and affairs.[11]

Those who favoured a purely commemorative option worried about the gradual erosion over time of the monument’s meaning. For them, all memorials needed to remain unsullied by mundane considerations.

Those who favoured a purely commemorative option worried about the gradual erosion over time of the monument’s meaning. For them, all memorials needed to remain unsullied by mundane considerations.

The Great War, as has been noted elsewhere, led to changes in the role of women, both at the front and back home. While progress in some areas – greater work opportunities, partial political enfranchisement – were made, it is equally clear that equality had not yet been achieved. The energy of women still tended to be channelled into certain areas of endeavour. One of the most important of these was commemoration. Groups like the Women’s Patriotic League and the Imperial Order of the Daughters of the Empire were most active in organizing commemorative efforts.

A case in point was the IODE memorial, which was eventually unveiled in 1923 . The Expositor described the inauguration in glowing terms:

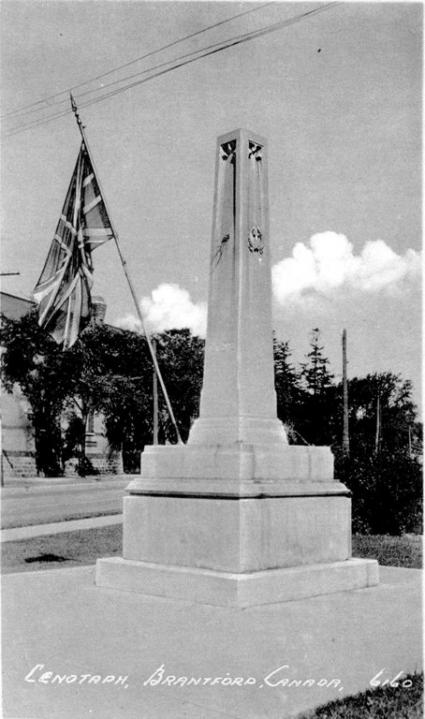

The morning sunlight streamed in benediction upon the vast assemblage that gathered Sunday to participate in the annual I.O.D.E. Armistice service, and fell upon the shrouded cenotaph, whose unveiling they were about to witness. Drawn up on the armories gore, were the Dufferin Rifles and band under Bandmaster Johnson, Brant Dragoons, Brantford Machine Gun Company, the G.W.V.A., and the pupils of the Mohawk Institute. The eight standard bearers of the Brantford chapters of the I.O.D.E., Mrs. Cameron, Miss Gilkison, Mrs. Newman, Mrs. M. Paterson, Mrs. Popplewell, Miss Craddock, Mrs. Earl Smith, Miss Murray Thorburn, with their silken standards, stood by the side of their respective regents.

The women are being described in terms that mirror the military representatives. They should be accorded the same respect and honour that those who fought on the battlefields were given.

Drawn up immediately in front of the cenotaph was the guard of honor, which presented a very smart appearance under Capt. Bolt, Capt. Lloyd Colquhoun and Lieut. Brooks. It was an impressive sight. Promptly at 10.30 Capt. (Rev.) W.G. Martin preluded the service with the invocation followed by the reading of a passage of Scripture. He then asked Mrs. M.A. Colquhoun, as representing the mothers, who had lost sons in the war to unveil the cenotaph. Mrs. Colquhoun stepped forward and loosened the Union Jack, which veiled the shaft and the sunlight seemed to illuminate the words graven on its base, “Let those who come after, see to it that their names be not forgotten.” A shaft of appealing simplicity and beauty was revealed, from standard rests at the sides, floated two Union Jacks, while above was the symbolic torch, whose brightness shall serve to remind the passerby that the living flame, which it typifies burns in human hearts and that the supreme sacrifice of the flower of Canadian manhood has not been made in vain.[12]

Women, most often cast in the role of mothers and nurturers, were often key players in dedication ceremonies. They might not be given the right to speak but they often stood as mute reminders of the suffering caused by the war.

Women, most often cast in the role of mothers and nurturers, were often key players in dedication ceremonies. They might not be given the right to speak but they often stood as mute reminders of the suffering caused by the war.

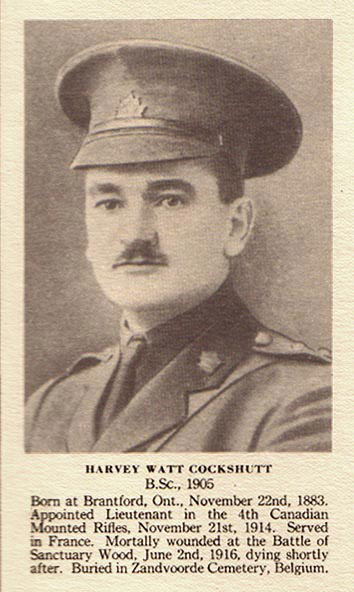

As the preceding examples demonstrate, the efforts to commemorate the Great War were largely democratic. Most frequently, monuments were raised to honour all of the dead, regardless of their position in pre-war society or the rank they attained during the war. However, given the persistence of socio-economic divisions in local society, it remained true that certain individuals might receive special attention. Such was the case with Harvey Watt Cockshutt, only son of the founder of the Cockshutt Plow Co. in Brantford. Harvey was killed in the disastrous Battle of Mont Sorel in June 1916. The Rev. W.G. Martin, pastor of the Congregational Church, officiated at the ceremony to inaugurate a YMCA girls camp in his honour, and:

…in a few words, every one of which was full of meaning, Mr. Martin made clear the importance of the event. Throughout the land, he said, numerous memorials were being given for soldiers who had fallen, but none was more beautiful or more fitting than the opening of this camp for the girls. Mr. Martin said he regretted that Mrs. Cockshutt was not there to express to her personally some appreciation for her kindness and thoughtfulness, for here was the realization of a dream of ambition of the highest order, for out of her sorrow she was giving joy to theirs, out of loss, increase out of death, life. The beautiful camp would be a perpetual memorial to her son, and he thanked God for the giving of such a gift.[13]

After the Reverend spoke, it was the turn of George Wedlake. He eulogized the young Cockshutt, explaining:

When the war broke out Harvey Cockshutt’s words were: ‘I don’t want to go, but I feel it is my duty to go,’ and he went. And there one morning in June, 1916, in a tremendous assault, he was wounded, and his comrades built a parapet of sandbags about him, but the Germans came on and they were obliged to leave him, and he was never heard of again until February, 1917. His mother in giving this to the Y.W.C.A., Brantford, was keeping alive the memory of the sacrifice of her only son. [14]

Even when it came to as controversial a figure as Douglas Haig[xv], Brantford showed reverence and respect. In August 1920 City Council proposed:

That the park, commonly known as the swimming pool park, be named Earl Haig Park, in order that Brantford many permanently honor the memory of this great soldier, who not only gave such great leadership during the Great War, 1914-1918, but devoted the remainder of his life in the interests of the Empire’s service men, now returned to civic life.[16]

Clearly, remembrance was a sacred duty in Brantford. Even before the war ended, efforts to recognize the valour of local men and women started. However, after the war was won, these efforts gained speed.

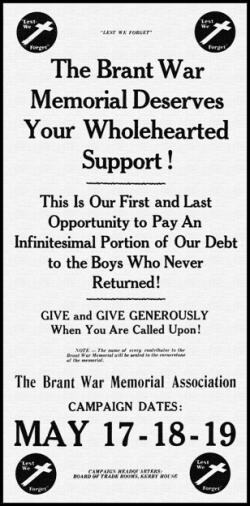

The ultimate recognition of the sacrifice of all those who served was, in the minds of many, the Brant War Memorial. While the notion of a fitting tribute to those who had served first arose immediately after the war, it was only in that proponents got organized.[17] Still, as the souvenir booklet produced for the dedication of the monument contended, by 1921 “citizens of all classes” were eventually lined up behind the effort to honour those who had served.[18]

Many of the City and County’s leading citizens took up the cause of a memorial, forming an association for that purpose. The Executive Committee was comprised of Judge Alexander Hardy (Pres.), John H. Spence, Mrs. C.W. Livingston, A. K. Bunnell, Reginald Scarfe and George Hately (succeeded after his death by F. W. Thompson). Other representatives of the region’s industrial and political elite were regular members of the Association.[19]

There were three main issues to sort out in recognizing the men and women who served during the conflict: form, location and financing. On the first of these matters, there was considerable debate. Some favoured a memorial hospital. Others advocated for a new City Hall. In the end, a monument won the day. As the Expositor put it “There is one thing that must not be lost sight of, and that is, that it must be a soldiers’ memorial. Those who propose structures for the welfare of the community seem to talk as if it were a citizens’ memorial."[20] At least the choice of artist was less contentious. Who better to undertake this work than Walter Allward, architect of both Brantford’s Bell Monument (inaugurated in 1917) and the monument celebrating the Canadian victory at Vimy Ridge?[21]

When the Memorial Association presented its plan in 1923, its members tried to combine the best of the utilitarian and memorial approaches. The Association proposed the purchase of a plot of land adjacent to the Armouries, promising to locate a public park as well as the monument there. Funding would come from public subscription. However, it was not until the economic situation was improved – in 1927 – that the campaign was launched. [22]

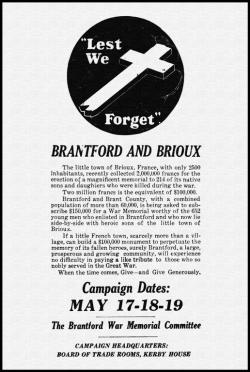

During that campaign, the Brantford Expositor included many appeals on behalf of the Memorial Association. Readers might be told that – echoing “In Flanders’ Fields” – to their hands “has fallen the torch” so ably kept aloft by the men and women who served (see left). Or, the local citizenry might be urged to “pay an infinitesimal portion of our debt” by supporting the fundraising appeal (see right). Remembrance was very clearly portrayed as a sacred act of keeping faith with those who had given all in defence of King and Country between 1914 and 1918.

As with a number of commemorative projects after the Great War, economic uncertainty meant that a good deal of time passed before the monument was finished. The War Memorial was not unveiled until the spring of 1933. In a ceremony that was presided over by the Earl of Bessborough, the Governor General of Canada, the City and County paid tribute to its sons and daughters who had participated in the Great War.

[1] “Odd Fellows’ Monument”, Brantford Expositor, November 8, 1917.

[2] “I.O.O.F. Memorial to Brothers Fallen in Great War Fittingly Dedicated by Grand Master – Rev. Walter Cox, Grand Master of Grand Lodge of Ontario, in Charge of Unveiling Ceremony in Mt. Hope Cemetery – Annual Decoration of Graves Also,” Brantford Expositor, September 9, 1918.

[3] Ibid.

[4] Paul Fussell, The Great War and Modern Memory (New York: Oxford University Press, 1975), 21-23.

[5] Soldiers’ Graves in Marked Plot – Movement on Foot to Erect a Memorial Shaft to Veterans,” Brantford Expositor, November 1, 1918

[6] “Memorable Unveiling,” Brantford Expositor, September 24, 1928.

[7] “Legion Community Service Was Attended by Thousands – Annual Veterans’ Service at Victoria Park Was Followed by Unveiling of Monument in Soldiers’ Plot, Mount Hope, Erected Under the Auspices of the Kith and Kin – Flowers Placed Upon Graves of Former Service Men in Mount Hope, Greenwood and St. Joseph’s Cemeteries”, Brantford Expositor, September 24, 1928

[8] “Memorial By Which The Soldiers’ Plot is Marked in Mount Hope Cemetery – Worth Tribute Indicates the last Resting Place of Dead Heroes Who Risked All for Canada and the Empire,” Brantford Expositor, September 29, 1928

[9] Utilitarian monuments were those – like parks, swimming pools and hospitals – that aimed to honour those who had served with useful public amenities. See Ken Inglis, Sacred Places: War Memorials in the Australian Landscape (The Miegunyah Press, 2008), 138-139.

[10] “New School in East Ward to be Called ‘Major Ballachey School’ – In Honor of Trustee Who Gave His Life in the Great War…” Brantford Expositor, June 6, 1919.

[11] “War Memorials (Editorial)”, Brantford Expositor, June 12, 1919

[12] “Armistice Day Anniversary Was Fittingly Observed – Unveiling of the Cenotaph, Erected by the I.O.D.E. Was Largely Attended – Mass Service in Temple Theatre – Services in Other Churches – Two Minutes’ Silence Generally and Reverently Observed at 11 o’clock,” Brantford Expositor, November 13, 1923

[13] “Dedication of Memorial Camp, Dover – Harvey Cockshutt Memorial Camp Formally Presented to Brantford Y.W.C.A. – Splendid Gift,” Brantford Expositor, August 19, 1920.

[14] Ibid.

[15] See John Scott, “‘Three Cheers for Earl Haig’: Canadian Veterans and the Visit of Field Marshal Sir Douglas Haig to Canada in the Summer of 1925” Canadian Military History 5, 1 (1996), 35-40. Although Haig was controversial, his men loved him, especially since he advocated for then in the post war.

[16] “Earl Haig Park is Named to Honor Great British Leader,” Brantford Expositor, April 16, 1929.

[17] Gary Muir, Brantford a City’ Century vol.1 1895-1945 (Brantford: Tupuna Press, 1999), 165.

[18] Souvenir of the Dedication of the Brant War Memorial, Thursday May Twenty-Fifth 1933 (Brantford, n.d.), 2.

[19] Ibid., 2

[20] The Brantford Expositor, Feb. 1, 1921.

[21] Souvenir of the Dedication of the Brant War Memorial, p.2.

[22] Muir, Brantford a City’s Century, 166.