The Halifax Disaster

On December 6, 1917, a terrible accident put an exclamation point on what had been a very difficult year for the Allies and for Canada in the War. Two ships collided in Halifax Harbour, resulting in the most powerful man-made explosion ever in Canada up to that time. There was a double connection to this area. In the first place, Adam Sandy a Six Nations veteran with 18 years’ experience in the Haldimand Rifles, had the misfortune to find himself on a Halifax pier that day. In addition, the terrible accident galvanized the people of Brantford, who mobilized to raise in excess of $15,000 as a result of the explosion.

In December 1917, a terrible accident provided a sad exclamation point to a year of loss characterized by mounting privation at home and increasing carnage on the battlefield. The collision of two ships in Halifax Harbour led to a devastating explosion and fire that killed more than 2,000 people and resulted in some 9,000 wounded and 6,000 homeless.

On December 6, the Belgian relief ship, Imo and French munitions vessel, Mont Blanc collided when the Imo, in contravention of standard practice in the busy harbour, passed a third ship on the port rather than starboard side. The larger Mont Blanc blew its whistle indicating that the Imo should divert but the relief ship countered with two blasts of its own, meaning that it would maintain course. At the very last moment, both vessels tried to avoid a collision but the combination of Mont Blanc’s hard left and Imo’s full astern could not avert a catastrophe. Imo's prow struck the starboard bow of Mont Blanc.

Almost immediately, fire broke out on board the Mont Blanc. The crew, well aware of the volatile cargo on board, quickly abandoned ship, rowing into Halifax with great haste. Unaware of the danger, men from HMCS Niobe and HMS Highflyer were dispatched in small boats to help fight the fire. The tug Stella Maris also attempted to assist the French ship. Meanwhile, on shore, a growing crowd of onlookers was gathering as a thick cloud of acrid smoke from the Mont Blanc hung over the city. A last ditch effort to tow the stricken Mont Blanc away from Halifax ended in failure.

At 9:04 the Mont Blanc exploded, resulting in the most powerful man-made explosion ever recorded to date. More than 1,500 persons died immediately. Others would succumb later to wounds caused by the fireball, the shrapnel it produced or collapsing buildings. There were even casualties due to the tsunami caused by the shock of the blast, a surge that reached 18 metres above the high water mark.

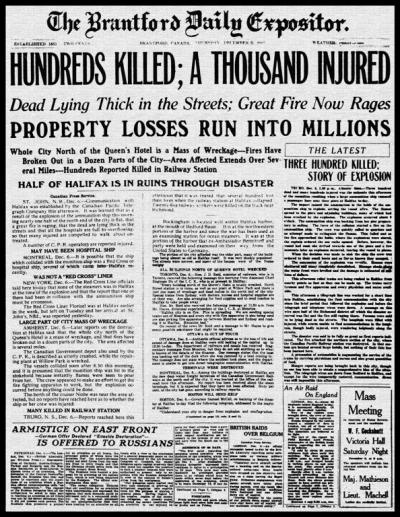

News of the tragedy in Halifax quickly reached Brant County. In a December 7 editorial, the Brantford Expositor opined that

News of the tragedy in Halifax quickly reached Brant County. In a December 7 editorial, the Brantford Expositor opined that

“To the great disasters of modern times – the Chicago fire, San Francisco earthquake, Galveston flood…must now be added the Halifax explosion.”

The senselessness of the disaster was only heightened by the fact that this

“…great tragedy, by which ammunition, intended to defeat the Huns has been devoted to the partial destruction of an Allied city, of millions of dollars [sic] worth of property, and probably 2000 lives, was not the work of an enemy, but the outcome of an unfortunate and appalling accident, by which greater damage was done than Zeppelin raid and submarine attack has thus far occasioned in any single instance.”[1]

Brantford sprang into action. On December 8 it was reported that

“An urgent meeting of the Board of Trade was held this morning, together with representatives of the Patriotic League, when it was decided to ask citizens to contribute blankets and warm winter clothing for men, women and children, including boots and stockings, and have these sent to the Patriotic quarters at the Y.M.C.A….”[2]

In addition, Mayor J.A. Bowlby immediately addressed his condolences to his counterpart in Halifax, also sending a cheque in the sum of $500 to help cover costs.

However, there were many in Brantford who felt that more should be done. There was wide support for a campaign to raise ten times the original amount sent by the Mayor. This led to a public subscription to aid the people of the devastated city. Typical of those determined to help in the wake of the accident was Joseph Ruddy. He declared “If we can raise $3,500,000 for the Victory Loan I don’t see why we can’t raise $5,000 for the sufferers and destitute in Halifax…”[3]

Eventually, the target of $15,000 in total was adopted with $5,000 each coming from the City, from local manufacturers and from the public subscription.[4] Ald. Dowling spoke for the people when he noted that “…the disaster was at our very gates brought about by the war.” Over the course of December, multiple acts of generosity illustrated the impact that the Halifax Explosion had on the people of Brantford, Brant County and Six Nations. Companies like Brantford Roofing Co., Dominion Steel Products and Goold, Shapley and Muir were quick into the ranks of contributors, with donations of $500 each. Waterous Engine Co. topped early donors with a pledge of $700. But perhaps most significant of all were the donations of ordinary citizens, like Mrs. G.C. Mackenzie, whose 25¢ may have been a greater hardship than the larger sums offered by the city’s great businesses.[5]

By December 12, total contributions to the Halifax Relief Fund had swelled to $13,165.14. An article appearing that day described the activity taking place at the Women’s Patriotic League’s rooms:

By December 12, total contributions to the Halifax Relief Fund had swelled to $13,165.14. An article appearing that day described the activity taking place at the Women’s Patriotic League’s rooms:

If anyone had lost faith in humanity and thought that the heart of the world was growing colder and more selfish, one look into the Women’s Patriotic League rooms, where they are packing parcels for the Halifax sufferers, would have convinced him to the contrary….

Kindly-hearted citizens, who believe in deeds, not words, motored to every part of the city to collect parcels that could not be sent. Representatives from every walk in life interested themselves in the good work, doctors, ministers, laborers, merchants, business men. Even little children were not to be outdone, who bravely carried huge parcels up two flights of stairs and gave of these best to the cause. One box revealed the heart of some unselfish child who had parted with perhaps her most treasured possessions – two dolls, a fair-haired dolly; gallantly guarded by a stalwart soldier of the Black Watch, who must have been just outfitted for a military wedding, as his uniform looked none the worse for wear.[6]

As time passed, in addition to valuable relief work on behalf of the victims of the explosion, firsthand accounts of the disaster began to appear. James G. Matthews, aboard the SS Canada related his experience in a gripping letter that appeared in The Expositor:

…I was down below in Mr. Dooley’s cabin (he is the O.I.C. of our wireless), and was just brushing my uniform as I was to leave for the mail in a few minutes. Most of our officers were up on the deck and I heard one of them remark that there was a ship on fire a little piece up the stream. The next moment we were all carried off our feet by the force of the explosion and it seemed as though our ship had been hit by a torpedo. I don’t remember very clearly just what really did happen for the first few minutes, but I remember seeing Mr. Dooley going through the door of the cabin, so I beat it too. The explosion lifted the ship up about three feet and the whole ship trembled just like a leaf. I then went up on deck and helped lower the life boats and get away the rescue parties.

Each boat left the ship in charge of an officer, and so I was sent ashore with a party of five seamen. The first thing that we did was to put out the fires in the buildings of the dockyard, and then Mr. Fields, one of our officers, with another party of men, and our party went to the magazines to help clear the large supplies of high explosives which were stored there. By this time the whole northern section of the city was one mass of flames and the fire was heading right along toward the magazines. Outside a few Imperial men who were already at work, the “Canada’s” men were the first there….After we got fairly well started we were joined by another bunch of seamen, and I was glad somebody came along, as it was getting to be all that I could do to lift the shells. We were told that we would be called as soon as the fire got too close but luckily that time never came. Once there was a scare, as somebody hollered that the magazines were going, and immediately everybody turned and fled, but an Imperial lieutenant off one of the ships stopped them and they returned to their work….

The loss of life was something awful and some of the sights are indescribable. The first house we searched through we came across a woman who was apparently in bed when the explosion occurred. Although she was dead there was a small kitten with her which didn’t seem to be hurt in the least, so one of the sailors took it for a keepsake. We worked all morning hunting out the wounded, and I think I must have seen hundreds wounded, and hundreds who were dead, and most of them so mangled that it would be impossible for anyone to identify them. The scenes were so horrible that one of our men went out of his head and has to be kept on board, but today he is much better." [7]

Accounts like this only spurred the local population all the more in its attempts to bring aid to the people of Halifax.

Accounts like this only spurred the local population all the more in its attempts to bring aid to the people of Halifax.

Finally, as Christmas neared, the Halifax Relief Fund attained its overall target of $15,000.[8] The reaching of this target represented a significant achievement in the context of a war-weary community, a fact not lost on the Brantford Expositor. Among the many sacrifices relief efforts engendered, the paper underlined the sacrifice of the children of St. Andrew’s church, whose Christmas pageant was highlighted by a statement about “…why this year there was no Christmas tree and no Christmas presents for the children. The children explained gladly and proudly that they had sent the money usually spent on their presents to the suffering children of Halifax.”[9] From the most influential captains of Industry to the tiniest children, people in Brantford and the surrounding region were deeply affected by the tragedy that took place in Halifax. Their efforts over an amazing three-week period made this abundantly clear.

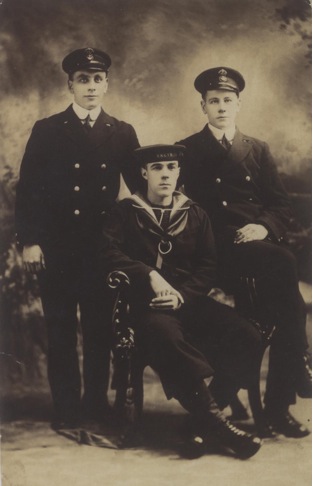

Alongside this fundraising, the human toll of the tragedy was still being calculated by the people of Halifax. On December 15, The Expositor reported that one of the 1,500 causalities of the explosion was Six Nations man, Adam Sandy. Sandy, a 43 year old labourer with 18 years past experience with the 37th Haldimand Rifles, enlisted with the 114th Battalion in January 1916. Most likely due to hospitalization and his age, Sandy did not go overseas with the 114th, but instead was transferred into the #6 District Special Services Company, and was posted to guard duty in Halifax.[10] Although listed as one of the missing on December 15th, his status was updated to “presumed dead” December 17th.[11] Due to the fact his death was not in an active combat area, his wife, Maggie Sandy, and three children were not eligible to receive a war gratuity for his time spent in active service during the war, or receive his memorial plaque and cross until 1926.[12] Although Adam Sandy does not have a marked grave, he is memorialized locally on Brantford’s cenotaph and the Six Nations Honour Roll, and in Halifax on the Halifax Memorial in Point Pleasant Park.[13]

[1] Editorial Brantford Expositor, December 7, 1917.

[2] “Appeal to Citizens For Warm Clothing – Blankets, Warm Winter Clothing, Boots and Stockings Needed at Once – Leave at Women’s Patriotic League Headquarters,” Brantford Expositor, December 8, 1917.

[3] “Speedy Relief to be Sent to Sufferers at Halifax – Board of Trade Decided to Request Opening of a Public Subscription List – City Council Asked to Send $5,000 from this City – Women’s Patriotic League Already Active, Brantford Expositor, December 8, 1917.

[4] “City Council Voted $5,000 to Sufferers at Halifax – Manufacturers of City Promised $5,000 in Cash or Suitable Goods and Board of Trade Named $5,000 as Objective of Subscription List – Council Held Special Session,” Brantford Expositor, December 10, 1917.

[5] “Generosity is Shown in Fund for Halifax – Manufacturers Exceed the Pledge of $5,000 They Set – Other Gifts,” Brantford Expositor, December 11, 1917.

[6] “Contributions for Sufferers – Gifts Received by Expositor for the Victims of Halifax Disaster” Brantford Expositor, December 12, 1917.

[7] S.S. “Canada” Was but 500 Yards From Big Explosion – But Not a Man Was Seriously Wounded, Force Going Over Their Heads – James G. Matthews Tells of His Experiences in the Great Disaster at Halifax – Removed Explosives From Magazines as Fire Crept Close, Brantford Expositor, December 14, 1917

[8] “Contributions to Local Funds – Halifax Relief Fund Now Over $15,000,” Brantford Expositor, December 24,

[9] “Sent Gifts to Halifax Relief – St. Andrew’s S.S. Did Without Christmas Tree This Year,” Brantford Expositor, December 28,

[10] Bob Richardson, “The Halifax Explosion and Adam Sandy Canadian Soldier,” Canadian Expeditionary Force 1914-1919, June 3, 2011. <http://canadianexpeditionaryforce1914-1919.blogspot.ca/2011/06/halifax-e... (16 February 2014).

[11] Brantford Expositor, December 15 and 17, 1917

[12] Bob Richardson, “Century Old Love Letters Found Hidden Inside Nova Scotia Home,” Canadian Expeditionary Force Study Group, May 30, 2011 <http://www.cefresearch.ca/phpBB3/viewtopic.php?f=5&t=8740&start=15> (20 February 2014). According to the Woodland Cultural Centre, two of Sandy’s children, along with their children, would be killed by Spanish Influenza in 1918.

[13] Veteran’s Affairs Canada, “Virtual War Memorial,” 14 March 2014 <http://www.veterans.gc.ca/eng/remembrance/memorials/canadian-virtual-war... (31 March 2014). Although Adam Sandy’s final resting place is officially unknown, researcher Bob Richardson has found some evidence to suggest that Sandy may have been interred among other unidentified explosion victims in Fairfax Cemetery in Halifax (Bob Richardson, “Century Old Love Letters Found Hidden Inside Nova Scotia Home,” Canadian Expeditionary Force Study Group, September 17, 2011 <http://www.cefresearch.ca/phpBB3/viewtopic.php?f=5&t=8740&start=15> (20 February 2014).