Recruitment

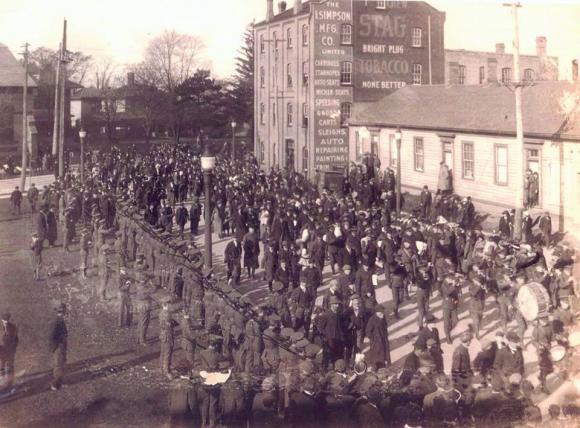

Efforts to recruit men for service in Europe began within a day or two of war being declared. The Brantford Expositor reported on August 6, 1914 that Brantford would be a key recruiting station for volunteers. The station was at the armouries of the 38th Dufferin Rifles and at that time the names and addresses of those willing to serve were recorded in anticipation of an order to mobilize.

On August 6, within the first two hours of recruitment, 144 men signed up. In the days that followed, there was a report of an estimated 700 men signing up for duty in one night.[1] This is all the more remarkable given that the population of Brantford at the time was about 27,000 with another 20,000 in Brant County.

Enlistment Statistics by Province/Territory[2]

Although recruitment on the Grand River territory was not as organized, and was completed on an individual basis, it was still met with the same enthusiasm as in Brantford and the surrounding counties. Alfred Styres, a Six Nations farmer, was tending his fields when he heard people in Hagersville were recruiting soldiers to fight overseas. Styres immediately arranged to have a neighbour take care of his crops and set out to Hagersville, where he enlisted in the 4th Battalion.[7]

While there was not an official policy banning First Nations enlistment into the Canadian forces before the war, the Canadian Militia Council, soon after war was declared, put a stop to First Nations enlistment, fearing “the Germans might refuse to extend to them the privileges of civilized warfare.”[8] This policy, however, was not relayed to regimental commanders and recruiters. Prior to 1914, many Six Nations men had received military training through either the 37th Haldimand Rifles, the Mohawk Institute Cadet Corps, or other Canadian militia units. Consequently, they were eagerly accepted for overseas military service.

These men volunteered for service, acting on their own or due to their training as soldiers. Men like Cameron Brant, and his cousins Frank Montour and Elgin Brant, were serving members of the 37th Haldimand Rifles when they enlisted in the 4th Battalion. Through this volunteering, some 60 men from Six Nations and New Credit enlisted shortly after the declaration of war.[9]

[1] Percy Gillingwater in The Brantford Expositor December 2, 1914. These figures should be taken with a grain of salt as Gillingwater was being interviewed by a journalist when he was in his hometown of Yarmouth, England.

[2] The table is adapted from Colonel A. Fortescue Duguid, Official History of the Canadian Forces in the Great War 1914-19 vol. 1.

[3] Statistics for Brantford from Souvenir of the Dedication of the Brant War Memorial Thursday May twenty-fifth, 1933 (n.d.), 4.

[4] In 1910, the population of Six Nations, Grand River Territory was 4,402 and this grew to 4,615 subsequently. An estimate of 4,500 in 1914 is not out of line with best scholarship on this question (see Sally M. Weaver, "The Iroquois: The Consolidation of the Grand River Reserve in the Mid-Nineteenth Century, 1847-1875" in Aboriginal Ontario: Historical Perspectives on the First Nations, Edward S. Rogers and Donald B. Smith eds. (Toronto: Dundurn Press, 1994), 187).

[5] According to the Department of Indian Affairs, 292 Six Nations men enlisted. This figure is not correct as early in the war, the DIA did not count First Nations enlistment closely (Duncan Campbell Scott “The Canadian Indians and the Great War” in Canada and the Great War, Vol. 3: Guarding the Channel Ports (Toronto: United Publishers of Canada, 1919) makes this clear). Asa R. Hill, in his speech delivered at the unveiling of the Bell memorial, states that the number of Six Nations men under arms was 300 (see The Unveiling of the Bell Memorial at Brantford, Ontario, on October the Twenty-Forth 1917). Paula Whitlow and Tammy Martin, of the Woodland Cultural Centre, are engaged in an ongoing research project on enlistment rates and estimate that the Six Nations total is even higher, hence the use of the figure of 325 here.

[6] As far as estimating the number of “eligible men” living on Six Nations, the best information available comes from a 1914 Sessional Paper written by Six Nations Superintendent, Gordon J. Smith, who states that there were 1,100 “able bodied” men on the Reserve.

[7] Duncan Campbell Scott “The Canadian Indians and the Great War” in Canada and the Great War, vol. III: Guarding the Channel Ports (Toronto: United Publishers of Canada, 1919), 297-298.

[8] James W. St. G. Walker, “Race and Recruitment in World War I: Enlistment of the Visible Minorities in the Canadian Expeditionary Force,” Canadian Historical Review 70:1 (1989): 7 and 4.

[9] Woodland Indian Cultural Education Centre Warriors: A Resource Guide (Brantford: Woodland Indian Cultural Education Centre, 1986), 17.