Conscription Crisis, Brantford, Brant

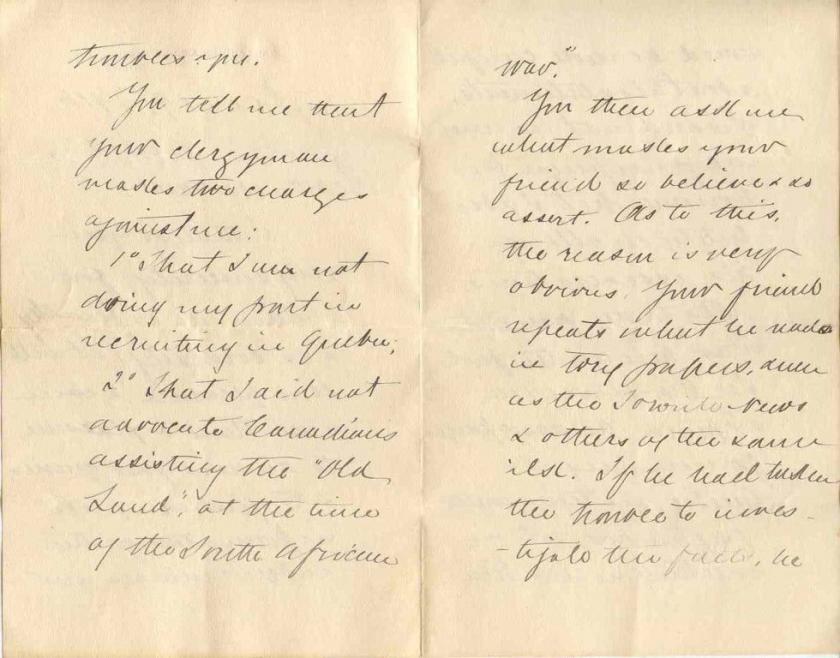

Years ago, Laurier Brantford received word that a donor from Burford had a letter from Wilfrid Laurier to her mother regarding the conscription controversy. Today, a framed copy of that letter sits below a portrait of the Prime Minister in the rotunda of the Carnegie building on campus. Hundreds of people likely pass it in any given week with no idea of the letter’s significance, for it marks an extremely turbulent moment in our history.

At the outset of the Great War, there was no problem finding willing volunteers to fight. As Eric Leed has pointed out in his masterful analysis of life at the front, No Man’s Land, “For many participants, August 1914 was the last great incarnation of the ‘people’ as a unified moral entity.”[1]

By 1917, the situation had changed markedly in all the combatant states. Canada was no exception. The key problem was that the number of casualties being suffered by Canadian forces was beginning to outstrip the number of new recruits coming forward. This was a situation that, clearly, could not be allowed to persist if Canada hoped to maintain its level of support for the wider war effort.

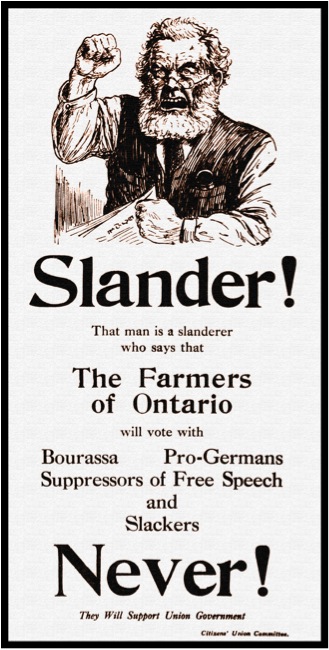

The military considerations were only complicated by various significant political considerations. On May 25, 1917, Conservative Prime Minister, Robert Borden, approached Opposition Leader, Wilfrid Laurier, with a request to form a coalition Union government. After a few days pondering the best course of action, Laurier, who opposed conscription and knew that this issue was looming, declined the offer. From the moment he did so (June 6), the die was cast. Liberals supportive of conscription (mainly from the West) began to break ranks and join the government; editorialists on either side of the debate began to ratchet up the rhetoric; the Government began to search for expedients that would shore up its support given the emotion that this issue was generating.

The Union Government eventually produced a number of pieces of legislation meant to address the situation at the front (as well as back home). The most controversial of all the legislation was the Military Service Act. Passed by the House of Commons on July 24 and entering into effect on August 29, 1917, it made all male citizens between the ages of 20 and 45 subject to military service.[2] In initiating the debate about conscription in Parliament following his visit to the UK, the Prime Minister had argued:

We have sent 326,000 men overseas in the Canadian Expeditionary Force. Including reservists in British and Allied armies, and men enlisted for naval defence, 360,000 men at least have left the shores of Canada. It is a great effort, but greater still is needed. Hitherto, we have depended upon voluntary enlistment. I myself stated to Parliament that nothing but voluntary enlistment was proposed by the Government. But I return to Canada impressed at once with the extreme gravity of the situation, and with a sense of responsibility for our further effort at the most critical period of war. It is apparent to me that the voluntary system will not yield further substantial results. I hoped that it would. The Government have made every effort within its power, so far as I can judge. If any effective effort to stimulate voluntary recruiting still remains to be made I should like to know what it is….All citizens are liable to military service for the defence of their country, and I conceive that the battle for Canadian liberty and autonomy is being fought to-day on the plains of France and of Belgium.[3]

With the creation of the Military Services Act Borden staked his future on the conviction that there was no other way forward.

Reaction to the Act was swift and fierce. Quebec Premier, Henri Bourassa asked “French Canadians are being exhorted to fight the Prussians of Europe in the name of religion, liberty and loyalty to the British flag. But shall we allow Ontario’s Prussians to impose their domination at the very heart of Canada’s Confederation, aided and abetted by the British flag and British institutions?”[4] Meanwhile, there were riots in a number of communities across Canada in response to the implementation of conscription.

There were significant pockets of resistance to conscription in many sectors of the population. Among farmers, urban workers and pacifists the measure was deeply deplored. A measure of the dissatisfaction aroused by the Act could be found in Brantford, where the local Trades and Labour Council, once very supportive of the war effort, now expressed doubts about conscription.

There were significant pockets of resistance to conscription in many sectors of the population. Among farmers, urban workers and pacifists the measure was deeply deplored. A measure of the dissatisfaction aroused by the Act could be found in Brantford, where the local Trades and Labour Council, once very supportive of the war effort, now expressed doubts about conscription.

By the end of the year, the Labour Council had not only expressed doubts about the wisdom of compulsory military service but had decried military training in the schools, which it believed “…inculcated a spirit of military jingoism in the country at a time when the Allies were fighting German militarism…”[5] The Council had also thrown its support behind the firebrand Independent Labour candidate, Morrison Mann McBride in the 1917 federal election. Though he was not successful, McBride polled a surprising number of votes and, shortly thereafter, was elected mayor of Brantford.[6]

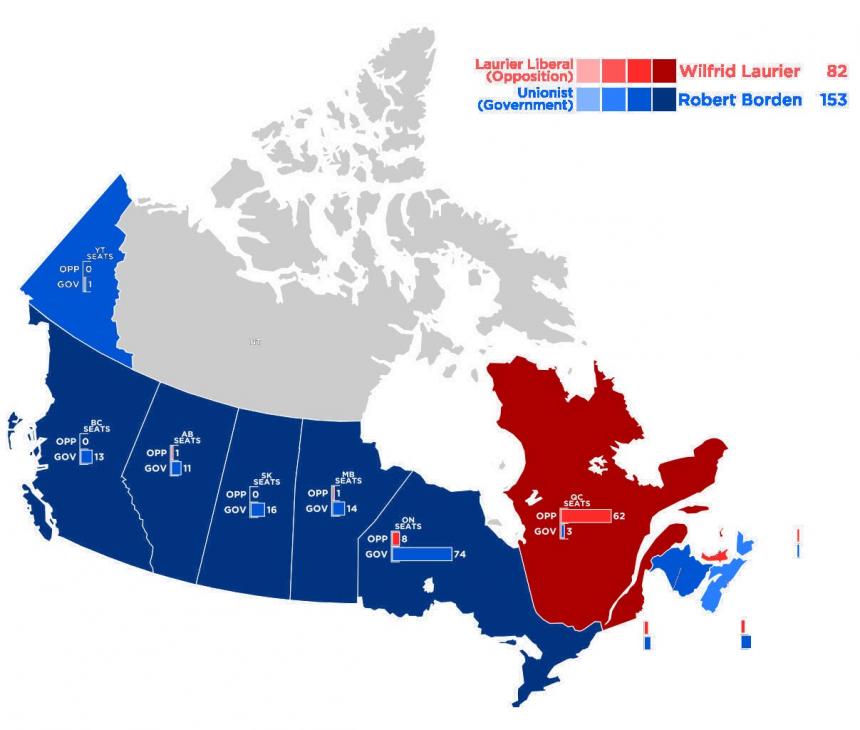

The debate over the Military Service Act set the stage for one of the most tumultuous federal election campaigns ever: the “Khaki” election of October 1917. The opponents of conscription were not exclusively francophone Canadians. However, the most glaring divide in Canadian society with respect to conscription was definitely the one separating Quebec from the rest of Canada. A quick look at the electoral map of Canada in the wake of the 1917 election (see Figure 4) makes this absolutely clear. The Unionists swept every province but Quebec and P.E.I., winning 153 seats to the Liberals’ 82. In Quebec the Opposition won a resounding 62 of 65 seats available. Having said this, the seat totals mask a more divided response across the nation. As one textbook puts it “The popular vote suggested greater division outside Quebec than the seat totals suggest. Civilian voters in the Maritimes gave a slight majority of their votes to anti-conscription candidates; even in Ontario, anti-conscriptionists won almost 40 percent of the civilian vote.”[7]

The debate over the Military Service Act set the stage for one of the most tumultuous federal election campaigns ever: the “Khaki” election of October 1917. The opponents of conscription were not exclusively francophone Canadians. However, the most glaring divide in Canadian society with respect to conscription was definitely the one separating Quebec from the rest of Canada. A quick look at the electoral map of Canada in the wake of the 1917 election (see Figure 4) makes this absolutely clear. The Unionists swept every province but Quebec and P.E.I., winning 153 seats to the Liberals’ 82. In Quebec the Opposition won a resounding 62 of 65 seats available. Having said this, the seat totals mask a more divided response across the nation. As one textbook puts it “The popular vote suggested greater division outside Quebec than the seat totals suggest. Civilian voters in the Maritimes gave a slight majority of their votes to anti-conscription candidates; even in Ontario, anti-conscriptionists won almost 40 percent of the civilian vote.”[7]

After the election, the violence associated with conscription gradually subsided. However, it boiled over once again in the Spring of 1918. A young man was detained at a Quebec City bowling alley because he could not produce his conscription registration papers. Soon an angry mob was retaliating by looting army offices and smashing the windows of English shops. Ottawa reacted by sending in troops (from Toronto). On Easter Monday, “…a few soldiers, trapped in a square and pelted with ice and snow, opened fire. Four civilians were killed; many were injured.”[8] It is not an exaggeration to say that English and French Canada had not been more divided since the trial of Louis Riel in 1885.

It was not long before the War was over. Borden had hoped to generate 100,000 fresh troops as a result of conscription. In this he was successful. Of the 401,000 who were called up, 99,651 were with the CEF at war’s end. In the words of the military historian, Jack Granatstein, “Compulsory service was politically divisive for a generation and more afterwards but it successfully produced reinforcements when the voluntary system had broken down. Readers will have to judge for themselves if the military advantages outweighed the political costs.”[9]

[1] Eric J. Leed, No Man’s Land: Combat and Identity in World War I (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1979), 39.

[2] 7-8 GEORGE V., CHAP. 19., An Act respecting Military Service (August 29, 1917); available at https://archive.org/ details/MilitaryServiceAct1917canada.

[3] Canada. Parliament. House of Commons. Debates of the House of Commons of the Dominion of Canada. 12th Parliament, 7th Session (January 18, 1917: September 20, 1917). Ottawa: J. de Labroquerie Taché, 1918, p.1541.

[4] Le Devoir, April 20; quoted in Mason Wade, Les Canadiens français de 1760 à nos jours, tome II (1911-1963) (Ottawa: Le Cercle du Livre de France, 1963), 160.

[5] The Brantford Expositor, April 5, 1917.

[6] Gary Muir, Brantford: A City’s Century vol.1 1895-1945 (Brantford: Tupuna Press, 1999), 135.

[7] Margaret Conrad and Alvin Finke, Canada: A National History (Toronto, Longman, 2003), 365

[8] Desmond Morton, A Military History of Canada (Toronto: McClelland & Stewart, 2007), 157.

[9] J.L. Granatstein, Canada’s Army: Waging War and Keeping the Peace 2nd ed. (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2011), 128.