BX September 11, 1916

125th Battalion Received Weekend Leave Soon After They Reached Bramshott – British-born Went “’Ome,” Canadians to London – Hearty Welcomes Given to Brants on Reaching Liverpool and Camp – Local Officers Convalescing in London Were Met – Lieut. Harold Staples Brewster Joins the Aviation Corps – Local Officers Who Went Into Ranks Receive Commissions Again

August 27, 1916

London, England

On Thursday, Aug. 24, the 125th Brant Battalion started its six days leave from Camp Bramshott. Only sufficient time was allowed to get the battalion nicely settled in its new home, officially inspected by the camp commander and his staff and welcomes paid, before half the battalion was given its customary holiday on arrival in England. A great many of the Brants started immediately for their homes, some going to Ireland, others to Scotland, and a great many to all parts of England.

The Canadian born, having few friends or relatives here, set out like so many sheep for Old London, and with the sheep I reached the metropolis too.

Having been in London before it has been particularly interesting to note some of the changes which have been occasioned by the war. In the first place everything is business, i.e., the old frivolity has disappeared. People’s faces spell determination and one receives the impression that there is somewhere near a huge burden which everyone must cooperate to the utmost in carrying. Cafes and swell restaurants have lost their glitter, and although they are still doing business it is in a saner and more sensible manner.

London in Darkness

At night the entire city assumes a somber attire. Other than automobile lamps, searchlights are apparently not allowed on motors, and a few lights in store windows, the city is practically in total darkness. There are a very, very few street lamps, but these are shaded so heavily that they give almost no light. When crossing the street at night one almost takes his life in his hands, there are so many vehicles and in the darkness it is very confusing to tell which way they are moving.

The war has branded London in a much more serious way, too. On all sides wounded officers and men are to be seen, some seriously, and some bearing practically no traces of their injuries. Many old buildings, schools, etc., have been resurrected for military hospitals, and I have seen several motor ambulances conveying soldiers lying on stretchers, and attended by some kindly and tender Red Cross nurse.

In the theatres several of the largest of which have closed their doors on account of the war, the stamp of the war is conspicuous. ‘Tis true, the audiences are large, but they are composed almost entirely of women and soldiers, the latter being either wounded and convalescing or on leave.

Women do Work

Another evidence of the war is to be found among the women. The fair sex in England, which has earned for themselves an undying reputation for their Spartan, self-sacrificing efforts during the war, are driving motor trucks and delivery wagons in the heart of busiest London. The famous penny busses are still driven by men, but the conductors are invariably young girls, garbed in a simple business like linen suit. They handle their tasks like veterans. In hotels, especially those of the higher class, business is still being conducted, but on less pretentious scales. The little finished touches and polish are lacking, the necessary things alone being available. The service in hotels and restaurants has highly deteriorated, the old experienced hands now doing the work of real men at the front. Small lads of 13 or 14 years are being used in hotels to do work of men who can perform their military service.

A Zeppelin Raid

Last night a Zeppelin raid touched the outskirts of the vast metropolis. In great headlines the morning papers tell of the Bosches’ visit, but little concern is manifested. Either the people have become accustomed to the visits of the night marauders, or else they have confidence in the steps which have been taken to fight the Zepps. Not since last October, when Zepps visited the very heart of London, dropping bombs along the strand, and being fired at from all angles by the specially fitted, high elevation guns, have the people of the city really felt the terrible reality of the Zeppelin bombs.

London is gaily alive with soldiers in addition to the imperial troops, Canadians, Australians and new Zealanders are to be seen on all sides. An officer can scarcely walk five paces without being called upon to acknowledge a salute. French officers, Belgians and an occasional Italian soldier are also encountered.

Among the great military throng, a few familiar faces appear occasionally. In the first place nearly a third of the 125th is here on six days’ leave, and it surely is good to see some of our own boys.

Brantford Personals

In fact, I think I could write a fair column of personal notes for your military society page. Here are a few:

Looking over the register of the Hotel Cecil here yesterday I espied the name of Lt. Harold S. Brewster. Lieut. Brewster, whom I met later, is on two weeks leave from the Royal Canadian Regiment with which he has just completed ten months in the trenches. He tells me that for considerable time his regiment was in the famous Ypres salient, where the cross fire from the two flanks and front was mighty hot at times. Harold considered himself very lucky to be here to tell the tale. He has succeeded in getting his transfer from the R.C.R.’s and will shortly commence a course in aviation at Reading, a few miles from London.

Shortly afterwards, one of our party, Captain Bingle encountered Lt.-Col. Mac Colquhoun, who apparently is on his way back to his regiment in France. He was in a great hurry at the moment, and there was not much opportunity to chat.

Yesterday afternoon, walking along by Trafalgar Square, I bumped into Lieut. Art Bishop who has had a varied experience since returning to England after his few weeks’ furlough at his home in Brantford. Art tells me that he has had a rather tough time of it lately, despite the fact that he looks remarkably well. Since October when he rejoined his regiment he has been in the Balkans, until this summer the heat was too much for him. He left for Malta where he remained for five weeks before proceeding to London where he now is under the doctor’s care.

Yesterday Sergt. Jack Raymond of the Brants, returned from a short visit at West Sandling Camp, where he had a few hours with his brother, Corp. “Glad” Raymond, formerly of the 58th Battalion and latterly on the pay office staff. “Glad” left yesterday to rejoin his battalion in France.

Major Frank Hicks, who was wounded recently in the leg, is also in London. He is in hospital at 50 Weaymouth Street, and expects, I am told, to return to his home in Brantford in about one month.

Major “Bert” Newman of the 19th Battalion is also in England and has arranged to meet his brother, Major W.F. Newman, of the Brants, in London during the latter’s leave here.

Altogether it can scarcely be said that one feels a perfect stranger in Old England now. All this that I have written has had little to do with what I started out to tell about.

The Trip to Bramshott

My last letter to The Expositor brought the 125th Battalion within a day’s run of Liverpool and from that date, August 17, till now, August 26, there is a considerable gap.

Looking back about ten days our boat brought us almost within hailing distance of land in the early afternoon of Friday, August 18. A government pilot boarded our ship, the Scandinavian, a few miles from our dock in Liverpool, and at that point our destroyer, No. 48 left us, sending a heartily “good luck” message, for which our lads expressed their gratification by loudly cheering as the destroyer steamed proudly past us into Liverpool.

At 6.20 p.m. we were “alongside” and shortly afterward the battalion was tucked away in the “pill-box” English coaches, bound for Bramshott Camp. Eight men to a compartment,Approaching the harbor the Canadians were surely given a hearty welcome. Steamboats and tugs, plying past us whistled lustily to us, and along the banks of the Mersey River, as we neared our landing place thousands of people waved their handkerchiefs vigorously and shouted a glad welcome to us. together with packs made things rather crowded, but who cared? To some it was “’Ome,” to others it was novel and funny. A long, tedious trip followed and sleep was practically impossible. From 7 p.m. on Friday we were jerked and jiggled about, until we reached our destination – Liphook – a small, quaint English village, at 5 o’clock the next morning.

Here we detrained, tired and weary. It was raining. A two and a half mile hike, with packs and all, followed. It seemed like 40 miles, but the lads, though tired and hungry, whistled and sang as they plodded along, as though in a new world. In an hour Bramshott camp came into view.

Bramshott Camp

Bramshott camp, located on a main highway about 41 miles from London and 23 miles from Portsmouth, is one of several camps in England set aside for Canadians. It is situated in the heart of a beautiful stretch of hilly, English country, and the panorama seen from the 125th’s parade ground is magnificent.

There are practically no tents, officers and men being quartered in “huts,” which resemble summer cottages more than huts. Each hut, built of frame, well elevated from the ground, clean and airy, provides accommodation for about 30 or 40 men, the officers and sergeants having separate quarters of their own. Each man is supplied with a “palaise” or mattress, and a wooden cot, and no complaints are heard. Excellent accommodation is also provided for lectures, etc, and from a sanitary standpoint Bramshott leaves nothing to be desired. The English rations are satisfactory and the men have stepped down from the excellent fare provided on the Scandinavian to the camp board very graciously. It was feared that the lads were being spoiled on board ship, but they are very content.

Bramshott camp is commanded by Brig.-Gen. Heighen. It is but seven miles from Aldershot camp and many of our officers and men have been sent to Aldershot for special courses of instruction. At Bramshott, there are about 10,000 troops. In addition to the 125th, the 123rd, 124th, 116th, 109th, 103rd, 120th and 121st battalions are stationed there. Several battalions comprising the fourth Canadian division had just left the camp for France, prior to our arrival. A few lads of the 84th battalion, which has been split up into drafts, etc., are still to be seen.

Discipline is Strict

Speaking of training, the English methods are not vastly different from those in vogue in Canada. “Discipline” is at a premium, all ranks being held strictly within the bounds set by regulations. Training is more severe. Seven full hours each day comprises the time set aside for drilling and instruction. Reveille, sounds at 5.30 a.m., and there is a half-hour drill before breakfast. “Fall in” sounds again at 8.30 a.m., and we “carry on for 3 ½ hours till 12 o’clock. Work commences at 1.30 p.m. again and continues until 4.30 when, “nominally” at least, the day’s work is done. That, however, is merely nominally.

As regards to the future of the 125th, little can be said with any degree of certainty. One often hears that the Brants may comprise one unit of the proposed fifth Canadian division. Should that be the case, we would likely be in England for some months. What seems more probable is that the 125th should remain a depot battalion, retaining its identity in name only, and sending drafts as reinforcements for the firing line. All this, however, is merely conjecture.

Use More Officers

One important and welcome announcement has been made since our arrival here. Henceforth, battalions proceeding to the front will be allowed 16 additional lieutenants. The reason for this is that the subalterns commanding platoons are almost continually absent from their platoons, taking special courses, etc. The supernumerary officers will permit of an officer being on hand at all times.

Consequently Pte. Morison Smith, Sergt. Dean Andrews, Co. Quartermaster-Sergeant John Orr, all of whom formerly held commissions with the Brants, will be again given their officer’s rank immediately. Other subalterns in Canada will be called for, it is understood.

Commencing on Aug. 24 headquarters A and B companies were given six days leave of absence. The balance of the battalion will take its leave as soon as the first half returns. The purpose of the leave is to enable the Britishers in the ranks of the C.E.F. to have at least four days at their homes as soon as they arrive in England. At the same time, we Canadians are given a splendid holiday, and the vast majority of the Canadians are spending their outing in London.

Now I have reached the point where this letter both begins and ends.

H.B.P.

BX June 7, 1917

Restrictions on Food Supply in Old London – Brantford Officer Reports Keenness for Stray Lumps of Sugar – Bread Measured Out – No Officer is Allowed to Order a Meal Costing More Than 3|6 – Economy in Bread is Impressed Upon the People Everywhere

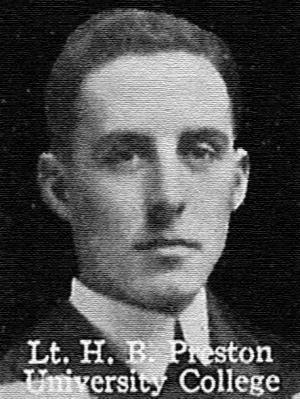

Lieutenant Harold Brant Preston, writing from London to the Expositor on May 19, thus refers to good conditions in the Old Land:

In the army one seldom realizes that the submarine war has had any effect whatsoever. Civilians may eat or civilians may starve, but the army gets its food just the same. That seems to be one strong point in favor of the high mucky-mucks in charge. Occasionally we are handed out a meat course minus potatoes, but that is really quite an exception. When that does happen some kind of cora fritter or a pastry ball is issued instead. Several months ago the bread issue on paper was cut down – at least such was reported in the battalion orders. I don’t think that anyone has ever noticed any difference. Recently, however, a shortage of sugar seems also to have spread to the army commissariat, and one or two meals each day are sugarless. Tea and coffee are swallowed without using sugar to sweeten the dose – but a little thing like that is neither here nor there. Whenever we get a chance in a restaurant or hotel we swipe any stray lumps of sugar and stick them in our pockets for future reference. I frequently count among my personal assets a couple of “none-to-clean” lumps which I have carried around for a few days. Outside of these few little things the food shortage hasn’t commenced to hit the army yet and I guess there isn’t much likelihood of it doing so for some months.

Bread Measured Out

But during my stay in London I began to realize that things were not normal. Of course one can get plenty to eat and I would not have enjoyed my leave as much if I hadn't been able to include in it several plenteous repasts. Still, there are some shortages and one cannot help realizing the fact when in London. In the first place, bread, which, as you know, is the staff of life to most people, and especially to me, is rated as the shortage of premier importance. “Eat less bread,” is the popular cry. One reads it everywhere and taxis carry a “Eat Less Bread” sign on their front glasses. London restaurants have orders to issue not more than two ounces of bread (which includes toast, rolls, etc.) to one person at one meal. Two ounces of bread is very little, and is measured out as a little better than an ordinary slice. At most restaurants no bread or rolls on the table to spoil one’s appetite while waiting for the soup to arrive.

In one restaurant where I had asked the waiter to bring me an order of poached eggs, “Sure, you can have poached eggs,” he said, “but no toast.” Another time I wanted a serving of Welsh rarebit. Of course that required a slice of toast for the cheese to lie on. I had previously eaten my two ounces of bread, so Welsh rarebit was out of the question.

Sugar a Luxury

Sugar in London is also a luxury. In many places it is dished out to each person in a little silver measure which is known as “Lord Devonport’s Measure.” Each person can, if necessary, have that much at each meal and that much would do little more than cover the bowl of an ordinary teaspoon. Sometimes, they hand out instead two tiny lumps of sugar, about the size of beans. Those things are much sought after and if stray ones are seen by the cup of the person who sat next to you, they usually find their way into your own pocket to be used when none can be obtained.

A Compressed Meat

In London, there is a military order which prevents restaurant keepers, etc., from selling food to officers, the total cost of which exceeds 3|6, that is about 85 cents. That may seem reasonable, but 85 cents is little enough when prices are so high, and especially to Canadians. At Simpson’s on the Strand, I saw “fillet fried sole” on the menu, and of course, like lighting I ordered that. It arrived and I disposed of it. Then I called the waiter and proceeded to order what I intended to be the major portion of my dinner. I could have no vegetables, no entrée, no dessert, and no sweats – no nothing. My fish had cost 3|6 and I was through. That was some meal. That order limiting the amount which officers can pay for meals is purely military, and has no application to civilians. It has nothing to do with submarines, but was made in order to reduce the unnecessary expenses of officers while on leave.

Liquors and Tobacco

As regards liquors and tobaccos there are also restrictions. Liquors are sold legitimately for five hours each day – from 12 noon till 2.30 p.m., and from 6.30 p.m. till 9 p.m. As regards tobacco, it is also illegal to sell tobaccos of any kind after 8 p.m., and one frequently finds that through lack of foresight one has no tobacco for the evening. All these things are taken in the best spirit by everyone. At times, they cause a little inconvenience, but other than that, as an ordinary visitor sees London, the submarine warfare has got a long, long way to travel before it accomplishes enough to really seriously affect the food problem in England.