Six Nations Conscription

With the announcement of the Military Service Act in May 1917, Native groups across Canada protested, but not for the same reasons as the rest of the population of Canada. For many First Nations, they had legal reasons, found within their treaties with the British and Canadian governments, exempting them from conscription into the Canadian forces. For the Six Nations, their exception from the Act was based on their allied status with the British Crown.

When the Military Service Act came into effect in May 1917, the Six Nations, like other Native groups across Canada, protested. Unlike the populations of Brantford and Brant County, the Six Nations’ response was based on their allied status to the British Crown. This treaty relationship with the British Crown, which has begun in 1664, recognized the Six Nations as independent from and equal to the British. The Six Nations argued that they could not be conscripted into the Canadian forces as they were an independent nation already allied to Britain. With this understanding of their position within Canada, it would be impossible for Canada to conscript the people of Six Nations, who were citizens of an independent ally.

When the Military Service Act came into effect in May 1917, the Six Nations, like other Native groups across Canada, protested. Unlike the populations of Brantford and Brant County, the Six Nations’ response was based on their allied status to the British Crown. This treaty relationship with the British Crown, which has begun in 1664, recognized the Six Nations as independent from and equal to the British. The Six Nations argued that they could not be conscripted into the Canadian forces as they were an independent nation already allied to Britain. With this understanding of their position within Canada, it would be impossible for Canada to conscript the people of Six Nations, who were citizens of an independent ally.

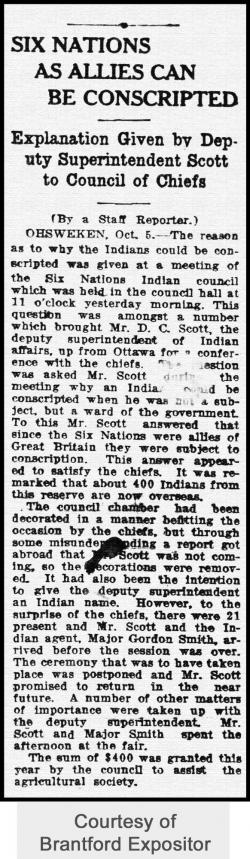

This stance openly challenged the Canadian government, which argued that, for the purposes of conscription, all First Nations people, including the Six Nations, were the same as everyone else in Canada.[1] The Department of Militia set up a conscription tribunal on the Grand River Territory under the direction of Chief J.S. Johnson. Johnson’s request to use the Six Nations Council House for the tribunals, however, was rejected by the Six Nations Confederacy Council of Chiefs as they did not want their council house used to force their men into the Canadian Forces.[2] The Chiefs further advised the people of Six Nations to refuse to register and to take no notice of the Military Service Act.[3]

Throughout 1917, the Six Nations used every means at their disposal to protest against the Military Service Act. In November 1917, the Confederacy Council sent delegations to Ottawa and even wrote appeals to the Governor General and King George V to stop Six Nations registration.[4] This protest against the Military Service Act took on a local flare in October 1917 during the unveiling of the Bell Memorial in downtown Brantford. Following their tradition of direct communication with representatives of the British Crown, Secretary of the Six Nations Confederacy Council Asa R. Hill took the opportunity to address the Governor General, the Duke of Devonshire, who was in attendance for the memorial’s unveiling. In his speech, Hill asked the Governor General to see to it that the Six Nations were exempted from the Military Service Act. Hill argued that the Six Nations had already committed 300 men to the war effort and, because the Six Nations population was small, he further requested that any future conscripts be permitted to stay in Canada for home defense rather than being sent overseas.[5] Prior to conscription, the Grand River Six Nations already had more men voluntarily enlist than any other First Nations community.[6] Although the Governor General responded to Hill’s speech, he did not say anything about the conscription of Six Nation men.[7]

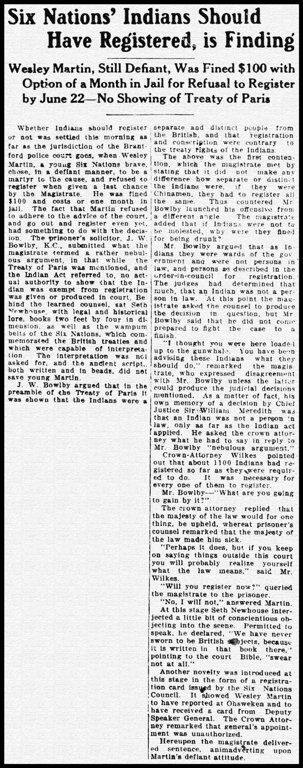

In January of 1918, the Governor General, countering the Canadian government’s position that First Nations people were equal to non-First Nations people insofar as conscription was concerned, issued an exemption for First Nations people from the Military Service Act. For the Six Nations and other First Nations groups, this exemption was not based on any treaty relationship they had with the British Crown, but instead on the fact that, since First Nations people were not allowed to vote in Canada, they were wards of the Crown.[8] This exemption, however, only exempted First Nations peoples from military service; they still had to show up to the conscription tribunals to register.[9] This was still unsatisfactory to the Chiefs of Six Nations as they saw registering under Canadian law as giving up their independent nation status. By June 1918, Six Nations member Wesley Martin was arrested in Brantford for failure to register.[10] Immediately, the Six Nations Confederacy Council volunteered to pay for Martin’s defence.[11] By July 12, Martin was found guilty of not registering and ordered to pay a fine, which the Confederacy Council agreed to pay on his behalf.[12] On September 19, 1918, The Brantford Expositor reported that Seth Newhouse, another member of Six Nations, had a warrant issued for his arrest after he failed to appear in front of a conscription tribunal.[13] This case does not seem to have been prosecuted.

In January of 1918, the Governor General, countering the Canadian government’s position that First Nations people were equal to non-First Nations people insofar as conscription was concerned, issued an exemption for First Nations people from the Military Service Act. For the Six Nations and other First Nations groups, this exemption was not based on any treaty relationship they had with the British Crown, but instead on the fact that, since First Nations people were not allowed to vote in Canada, they were wards of the Crown.[8] This exemption, however, only exempted First Nations peoples from military service; they still had to show up to the conscription tribunals to register.[9] This was still unsatisfactory to the Chiefs of Six Nations as they saw registering under Canadian law as giving up their independent nation status. By June 1918, Six Nations member Wesley Martin was arrested in Brantford for failure to register.[10] Immediately, the Six Nations Confederacy Council volunteered to pay for Martin’s defence.[11] By July 12, Martin was found guilty of not registering and ordered to pay a fine, which the Confederacy Council agreed to pay on his behalf.[12] On September 19, 1918, The Brantford Expositor reported that Seth Newhouse, another member of Six Nations, had a warrant issued for his arrest after he failed to appear in front of a conscription tribunal.[13] This case does not seem to have been prosecuted.

In response to this registration conflict, the Six Nations Confederacy Council began issuing their own registration cards, which stated that the cardholder was a member of the Six Nations and drew annuity money. The front of the card had an excerpt from the Treaty of Paris (1783) that stated Native peoples were not to be molested. This card was also signed by the Deputy Speaker of the Confederacy Council, Levi General.[14] According to the Canadian government, the Six Nations had no authority to issue these cards, which were deemed worthless in the eyes of the Federal government.

The fight against conscription seemed to strengthen the relationship between the Six Nations and the City of Brantford in some ways. During the registration problems faced by Six Nations, the City of Brantford continued to allow unregistered members of Six Nations to shop, eat, and travel within the city and some Brantford merchants continued delivering their goods to the Grand River Territory for sale. Mayor M.M. MacBride even sent a telegram to the Governor General asking for him to make a visit to the Six Nations and explain registration to them, as he felt that there were still some misunderstandings about the process.[15] As far as MacBride was concerned, Six Nations registration was a problem between the Federal government and the Six Nations and had nothing to do with the relationship between the people of Six Nations and the City of Brantford.

The conflict caused by the Military Service Act strained the relationship between the Six Nations and the Federal government. However, it should be noted that Six Nations were not the only group in Canada against conscription. Instead, they were just one of many groups seeking exemption including other First Nations groups, ethnic minorities, French Quebec, farmers, labourers, men with families, and fit men opposed the Military Service Act. In fact, nation-wide, nine out of every ten men that were called up for conscription in Canada applied for an exemption.[16]

GWCA Search for Lost Artifacts:

The GWCA is currently looking for any information about Six Nations men who were conscripted into the Canadian Forces during the First World War. The GWCA is also looking for any existing or photographs of Six Nations issued conscription exception cards. If you have any information about these or any other Brantford, Brant County, and Six Nations First World War artifacts or photographs, we would love to hear from you! Please e-mail us at info@doingourbit.ca.

[1] According to the Indian Act 1876, all First Nations people were to be considered wards of the Crown.

[2] Letter from J.S. Johnson to Duncan Campbell Scott October 16, 1917 (RG 10, Vol. 6768, File 452-20, Reel C-8512, War 1914-1918 – Correspondence Regarding the Conscription of Indians).

[3] Letter from Gordon J. Smith to Duncan Campbell Scott October 31, 1917 (RG 10, Vol. 6768, File 452-20, Reel C-8512, War 1914-1918 – Correspondence Regarding the Conscription of Indians).

[4] Various Letters, telegrams and petitions (RG 10, Vol. 6768, File 452-20, Reel C-8512 War 1914-1918 – Correspondence Regarding the Conscription of Indians).

[5] Transcripts of Speeches at the Unveiling of the Bell Memorial at Brantford, Ontario, on October the Twenty-Forth, 1917.

[6] Janice Summerby, Native Soldiers – Foreign Battlefields (Ottawa: Veterans Affairs Canada, 2005), found at http://www.veterans.gc.ca/eng/remembrance/those-who-served/aboriginal-ve....

[7] Transcripts of Speeches at the Unveiling of the Bell Memorial at Brantford, Ontario, on October the Twenty-Forth, 1917. According to F. Douglas Reville, the Duke of Devonshire’s response to Hill’s address was “fitting” (F. Douglas Reville, History of the County of Brant vol. 1 (Brantford: The Hurley Printing Company, 1920), 317).

[8] Draft of Legislation from the Governor General January 17, 1918 (RG 10, Vol. 6768, File 452-20 Part 2, Reel C-8513, War 1914-1918 – Correspondence Regarding the Conscription of Indians).

[9] Letter from Duncan Campbell Scott to Edwin Lee February 5, 1918 (RG 10, Vol. 6768, File 452-20 Part 2, Reel C-8513, War 1914-1918 – Correspondence Regarding the Conscription of Indians).

[10] Letters from Gordon J. Smith to the Department of Indian Affairs June 29, 1918 (RG 10, Vol. 6770, File 452-26 Part 1, Reel C-8514, War 1914-1918 – Correspondence Regarding the National Registration of Indians) and The Brantford Expositor, June 28, 1918.

[11] The Brantford Expositor, July 6, 1918.

[12] The Brantford Expositor, July 12, 1918.

[13] Letters and News Clipping from Gordon J. Smith to Duncan Campbell Scott September 19, 1918 (RG 10, Vol. 6770, File 452-26 Part 1, Reel C-8514, War 1914-1918 – Correspondence Regarding the National Registration of Indians).

[14] Letters from Gordon J. Smith to Duncan Campbell Scott July 6 and 8, 1918 (RG 10, Vol. 6770, File 452-26 Part 1, Reel C-8514, War 1914-1918 – Correspondence Regarding the National Registration of Indians).

[15] Telegram from M. MacBride to the Governor General July 17, 1918 (RG 10, Vol. 6770, File 452-26 Part 1, Reel C-8514, War 1914-1918 – Correspondence Regarding the National Registration of Indians).

[16] Jack L. Granatstein, “Conscription and the Great War” in Canada and the First World War: Essays in Honour of Robert Craig Brown, David Mackenzie ed. (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2005), 68.